Authorities raid a rumrunner’s boat

The rumrunner occupies a peculiar and romantic spot in the American imagination. Rumrunners, at least at their start in the Elizabeth Islands, were the good guys. They were not highwaymen or gangsters but fishermen, extraordinary boat handlers, and superb navigators. Their exploits demonstrated nerves of steel and enough daring and righteous indignation to satisfy the likes of Han Solo.

Rumrunners’ boats, like the Millenium Falcon, were not expensive yachts but tough, working fishing boats. Sometimes these were painted black and refitted with airplane engines for speed, and mufflers to diminish the engine’s roar and avoid detection. The modifications were done in small shipyards in out-of-the-way creeks and tiny harbors, mostly by local mechanics or the captain himself. As a group, they were totally opportunistic, and, really, in the face of their stark reality, who wouldn’t be?

Han and the Falcon

Life as a fisherman in the 1920s was not easy or lucrative. An oral history from island archives retells the story of one woman whose husband was a fisherman. She had several kids and could not afford the grocery store even for the most basic supplies. After school, her son hunted rabbits and squirrels to add to the larder. Her existence consisted of bone-crushing poverty and a life of endless work. Food came from the sea, the forest, and the garden. As romantic as this sounds to our 21st century sensibilities, it was nothing more than back-breaking work to preserve a measure of pride and family stability. The word grit comes to mind.

Then, one day, her husband came home with 10 brand-new ten-dollar bills and she went to the grocery store. From then on, the husband would disappear, usually in the dark of the moon. She would wait up for him, knitting. When he got home, she never asked questions; she simply accepted the change in their fortunes. Their life was better, not sumptuous, not perfect, but better. He was a rumrunner.

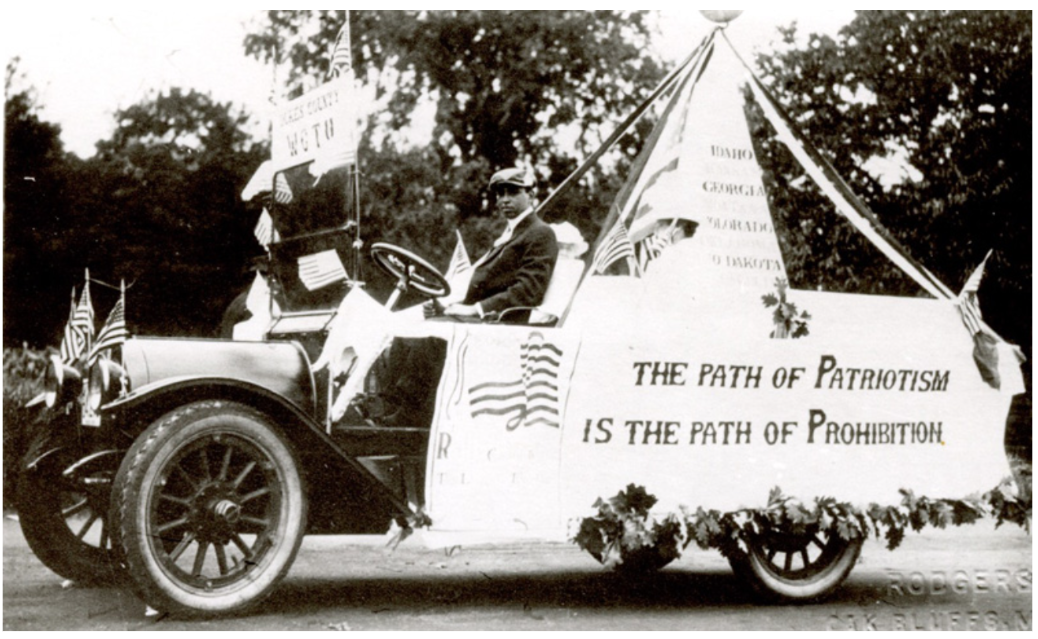

Rumrunning was the unintended consequence of the 18th amendment, which, in turn, was a response to women getting really tired of their husbands spending their paychecks in bars and taverns rather than supporting their families. The movement became entangled in evangelical fervor and class divisions, and ultimately was politized in the form of the amendment. Simply put, it became illegal to buy and sell liquor, which opened the door to rumrunning, or the illegal booze trade.

Campaign vehicle

In the early years of Prohibition, accomplished mariners marveled at how easy it was to make serious money. There were men like Bill McCoy, who inspired the term the real McCoy. Bill was impossibly handsome and charismatic. He was also an extraordinary mariner and businessman. He specialized in premium whisky and managed to buy it from offshore ships and resell it. His territory extended from Miami to Martha's Vineyard. He made a fortune and his name became known as the genuine article; if you bought booze from Bill, it was always the real McCoy.

The Real McCoy himself

Frank Butler and his high-speed boat, the Nola, became famous for outrunning every Coast Guard cutter between the Vineyard and New York City. He was a brash, daring individual with a personality that was larger-than-life who enjoyed respect and admiration among his fellow rumrunners at home on the island.

And these were but two of many that obsessed the American imagination during the roaring 20’s.

In 1923, the territorial waters limit went from three miles to twelve. What that meant was that the rumrunners had to go twelve miles offshore to meet cargo vessels (mostly Canadian and British) loaded with alcohol—spirits, wine, and beer were the most common—instead of merely three.

Rumrunners typically operated on moonless nights and always without running lights to avoid detection. They often hid their cargo by building false compartments in the bilge to house the crates or barrels. Fishermen would often disguise their cargo under their catch. They would go out at night, pick up contraband, and then go fishing, putting their catch on ice so it concealed their other cargo, thus maximizing profits.

Eventually, rumrunning became a mob activity. In fact, the mob’s toe-hold in New York City was a direct result of the early success of rumrunners. Eventually, the whole enterprise took on a violent and lethal cast. Gatling guns were mounted on boats and full-on shootouts were the order of the day.

On December 5, 1933, the 18th Amendment was repealed; with it came the end of rumrunning, closing a colorful but deadly chapter in our past.

Celebrating the Amendment’s repeal

-Bird Jones