It is a beautiful fall day here in Vermont, where we’ve had a rare bout of warm weather. The colors are stunning and it’s possible to put the garden to bed before the ground freezes. In just a couple of weeks, I’ll be at the Weybridge Town Hall, working the polling desk. In a town of 700 residents, elections are a chance to visit with your neighbors and, incidentally, to buy pies.

On Election Day, the elementary school sells homemade pies at the Town Hall to raise money for the library or the gym or something else they need. The kids park a table right as you walk in, and it’s just about impossible not to buy a pie from the seven-year-old salesfolks. The pies are pretty great; there’s usually a line at the door prior to the polls opening at 7am of voters making sure they get a pie before they’re all sold.

Election Day in Vermont is slow-paced, reasonably good-natured, and drama-free. It is a gift.

When thinking about the furor of our current election and all that it represents, it’s useful to once again swirl back down the whirlpool of history to the 1920s. In my last post, we took a look at the election of 1920, but what happened in ‘24 and ‘28? There were some real surprises.

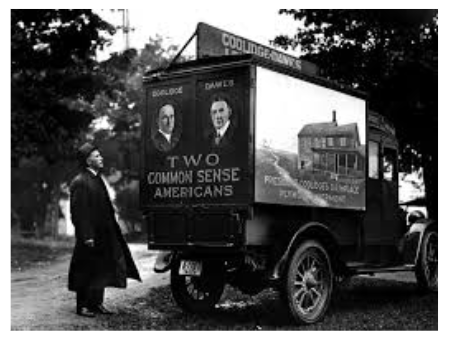

1924 Election

In 1924, the economy was humming along and there were no major crises. All was good in America. Republican Calvin Coolidge won the 1924 election by a landslide. His running mate, Charlie Dawes, would one day win the Nobel Peace Prize for restructuring Germany’s financial obligations under the Treaty of Versaille.

Dawes was unquestionably a fine politician, diplomat, and statesman, but he was also a composer whose real love was music. One of his tunes—”Melody”—greeted them at every campaign stop, played in the key of A major.

Another interesting candidate was Robert M. LaFollett, who ran as a Progressive in the same 1924 race. Since both Coolidge and Dawes were conservatives, the Left coalesced behind Fighting Bob (as LaFollett became known). His chief goal was "to break the combined power of the private monopoly system over the political and economic life of the American people" (Thelen, 1976, pg 182–184).

Fighting Bob advocated for cheap loans to farmers, a federal take-over of the railroads, the prohibition of child labor, and protection of all civil liberties. But his agenda was simply too much for the voters and his coalition too hard to manage, and thus he got 13 electoral votes and 16.6% of the popular vote.

1928 Election

In 1928, Herbert Hoover, a Republican, beat the Democratic challenger Al Smith, a former New York governor. The sweet economy of the last four years helped secure Hoover’s win, as Smith, a Roman Catholic, felt the sting of anti-Catholic prejudice at the polls.

Probably the most interesting candidate was Hoover’s running mate, Charles Curtis, a senator from Kansas and a member of the Kaw Nation. He was the first person of color and the first Native American to hold such a high office. An affable, principled man of compromise, he championed women’s rights and supported the Equal Rights Amendment.

Hoover (L) and Curtis

Born into a biracial family, Charles Curtis’s early years were heavily influenced by his grandmothers—one a member of the Kaw nation and the other a white settler. He spent equal time with both although the young lad mainly identified with his Kaw roots.

When the Kaw Nation was evicted from their lands and forcibly relocated to Oklahoma, young Charlie heeded his grandmother's advice. “I mounted my pony with my belongings in a flour sack and returned to Topeka and school.“

His was a surprising and complicated career as Curtis was a man who walked in two worlds. He learned to speak French and Kansa before he spoke English; he championed rights for women and he supported the right of citizenship and the right to vote for Native Peoples. However, he also supported assimilation and the boarding schools for Native Americans. Complicated.

Curtis’s success was largely due to his ability to compromise and work both sides of the aisle. He built relationships that were grounded in genuinely knowing folks—the names of their kids, what they liked and didn’t like. His affability won over voters.

Hoover and Curtis were defeated in 1932 by FDR. As we hurtle towards what’s looking like a very contentious election, it is helpful to pause and ponder, How does the past resonate in the present?

Perhaps one place to hear echoes of the past is in many of the candidates’ ability to operate out of a place of compromise. That was certainly true of Charlie Curtis as well as Calvin Coolidge. There’s also a thread, in both our current political climate and the environment of a century ago, of defining one’s moral compass as conservative, republican, or progressive.

Finally, there is the importance of our ability to vote. Voting is the only way we can shape how our problems get solved, and when and if our interests and rights are protected.

In the 1920s, women and Native People were only recently enfranchised (women got the vote in 1920, Native People in 1924 with the Snyder Act). We must remember lest we forget: it’s a privilege to vote and a privilege to work the polls. Of course, there are also pies and all that they represent—the best of who we are as a nation.

-Bird Jones