Film Poster. Directed by Byron Haskins

Too Late for Tears lays out a one simple yet diabolical premise: an unintended windfall—do you take it and run or turn it in? And so begins Jane and Alan Palmer’s demise, slow and sure.

The film jumps in with an unhappy couple headed for a dinner party along a twisty California road. They argue; Jane, played indelibly by Lizabeth Scott, grapples for the keys. Just as they are tousling over the car’s controls, flicking the headlights on and off, another car passes them and dumps a bag into the backseat of the quarreling lovers’ convertible.

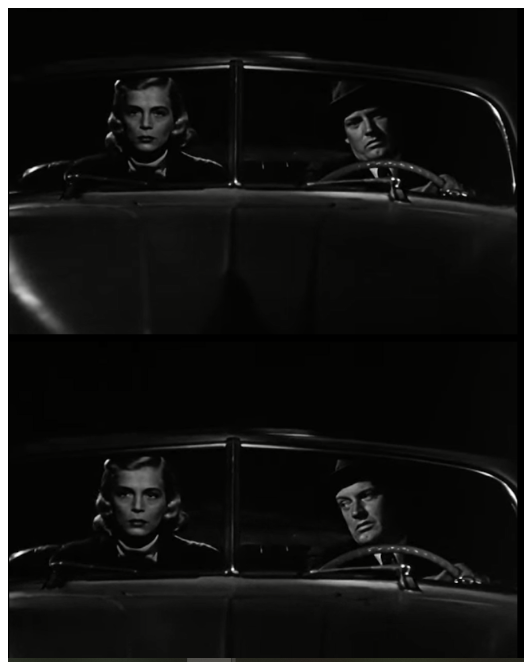

Jane will soon take the wheel and never let go

They stop long enough to discover that the bag is not just a bag but actually a bag of cash. Jane spots another car headed their way, deduces it must be the intended recipient of the money, and leaps into the driver’s seat. This is where she wrests control of the plot and she doesn’t let up for one single moment of the film’s surprisingly short run-time.

Alan the husband (Arthur Kennedy) has a chance to give up the money and, against his better judgment, doesn’t. But Jane knows exactly what she wants as soon as Fate dumps a load in her lap. We can see as much in her awe-struck greedy expression and how quickly she takes control. Jane's true crime in this film is taking what she wants when she wants it. And what does she do with it when she gets it? She runs, burning through anybody who stands in her way.

This movie is about what would happen if a femme fatale got everything she wanted, with the consequent trouble.

If only he had looked her once in the eyes

“I’ve tried to give you everything you've wanted, everything I could!” -Alan

“Yes, you’ve given me a dozen down payments in installments for the rest of our lives.” -Jane

Yowtch.

Lizabeth Scott slinks her way into the role of Jane Palmer in light-toned pencil skirts with matching jackets, blocky heels, and a pert shiny blonde bob waved just-so across her fetching forehead.

Ready for a life of crime or her shift as a stenographer

The reason Lizabeth Scott makes this such an unfading performance as Jane Palmer, immediately seduced by the Almighty Dollar, is her change from apple-pie housewife to murderous conniving temptress, an astounding and believable jump.

Femme fatales are usually seductive bar flies, sucking down cigarettes and winning over saps with a flash of skin. But not poor, put-upon Jane, bearing the burden of that bag of money and all of her ambitions. She takes men in much more subtly—a tug on his lapel, hiking up her modest skirt for an eyeful of knee, and, mostly, mesmerizing them with her watchful eyes and smoky low voice.

Looking at her one true love—sweet sweet cash

Jane Palmer never breaks out of her Suzy Q housewife persona when traversing the back alleys of a dark underworld, but keeps her collars firmly buttoned and her beret pulled down against any inquiring gazes. However, inside that sensible yet stylish purse is a loaded pistol, and she uses it with great alacrity despite being, as she admits to Danny in her scratchy alto, “a real-life bored housewife.”

The other big player in this film is Dan Duryea, who we’ve seen in so many noirs his face rings everyman-crime guy. Danny is introduced as a pretend-detective and gets right down to slapping Jane around until she confesses that she and her husband have his money. Because he isn’t a private dick, he’s the lowlife that the money was meant for on that dark twisty road.

Realizing who has the upper hand a little too late

Later, the original un-blissfully married couple—Alan and Jane—argue about what to do with the cash, locking it away until a consensus is met, and then Jane kills Alan. She says she does it by accident, that the gun fell out of her purse, but she barely flinches through the ensuing chaos of her husband’s murder.

You never see her shed a tear for anyone lost along the wayside, and it’s magnificent. The only time Jane gets seriously stressed is when anyone threatens to take away the cash. Because, if it’s one thing this noir does right, it illuminates how everyone has a capacity for very bad deeds if we love something more than is good for us.

Soon a man named Don shows up, Alan’s old pal from the Air Force (or so he says), and starts poking around, dating the only surviving morally true character—Alan’s sister Kathy—who has her hackles up about Jane, especially when a fictitious “other woman” is introduced as motive for Alan’s disappearance. Jane, never to be outdone, calls up an actual old Air Force buddy of her late husband’s to disprove the guy’s story.

Don and Jane play nice

Things get stickier and stickier until Jane finally gets her grubby mitts on the bag of dough and disappears, or so we think. The film then centers briefly on Kathy’s and Don’s chase and romantic entanglement, but we don’t care about them. The film perks up again with Jane somewhere in the desert, where a pushy cowboy tells her she’s sure to need some male protection. Boy, is he ever wrong. Did I mention she poisoned Danny, the criminal unlucky enough to cross her path with his bag of ill-gotten gains? Not a tear shed.

Too Late for Tears presents the same conundrum for Jane Palmer as a similar set of circumstances does for the female leads in Thelma & Lousie—they either conform to the world in which they exist or take to crime and its terrible reverberations. Lizabeth’s Jane isn’t too fragile for the world of Too Late for Tears, she’s too tough, trapped with a voracious appetite in a woman’s position.

This film was later released as Killer Bait in 1955, and then re-released as Le Tigresse in France, which is the most apt title of all.

Frankly, my dear, she just doesn’t give a damn

Although this is a story of a fatal decline into crime, it’s also a film about a woman finding out who she really is and that, even better, she likes it. Such a woman could not survive long amidst the Dons, Alans, and Dannys with whom she competes. It’s not that they best her in this particular race, it’s that she burns too fast and too bright, leaving little more than ash.

-MH